May 1

In Final Season, 'The Righteous Gemstones' Embraces Depravity Even as it Appeals to Christians

Krysta Fauria READ TIME: 4 MIN.

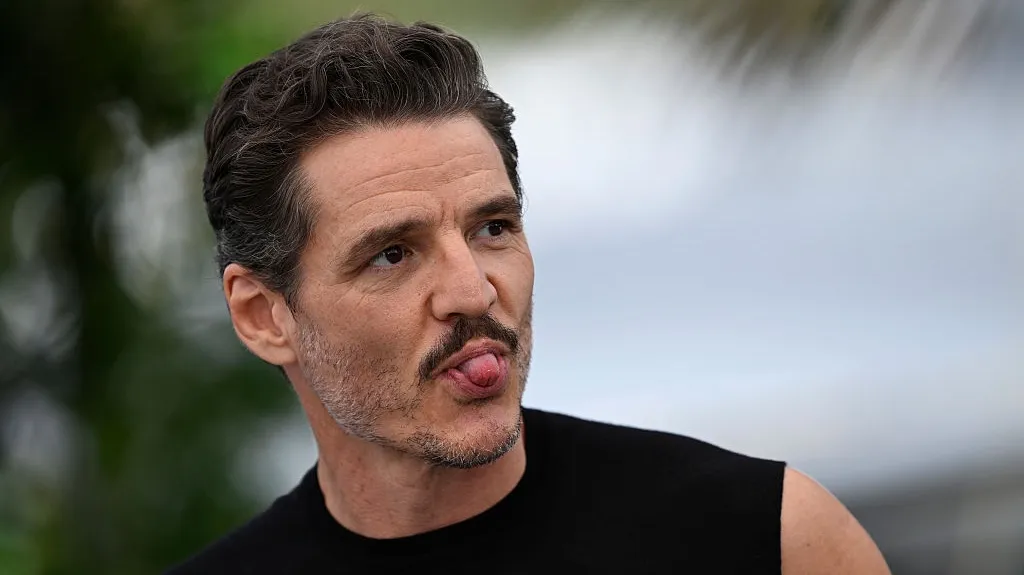

For a show about a Christian megachurch pastor and his nepo baby children – between the sex, violence and full-frontal nudity courtesy of Walton Goggins – the final season of "The Righteous Gemstones" is rife with its trademark depravity.

But Danny McBride, who stars in and created the HBO series, has always hoped it would speak to people of faith, even as he acknowledged his crude sense of humor might not be for everyone.

"My hope honestly with creating the show was that people who were religious would watch it. That, ultimately, they would understand that this isn't making fun of them, but it's probably making fun of people that they identify and are annoyed by," he told The Associated Press ahead of the fourth and final season's finale on Sunday. "A lot of people who come up to me, honestly, their first thing will be like, 'I go to church and I think it's funny.'"

McBride grew up in a devout Christian household in the South. His mom even led a puppet ministry when he was a kid. At some point, though, the 48-year-old decided churchgoing wasn't for him. But his interest remained, particularly as he began to learn more about megachurches after moving to Charleston, South Carolina.

"I felt like it kind of was reflective of America in a way that everything is sort of turned into a money game," he said. "The idea that like we could take something like religion and ultimately turn it into a corporation."

McBride's series follows widowed patriarch Eli Gemstone (John Goodman) and his three adult children, the eldest of whom is played by McBride. Although the series is steeped in modern evangelical culture, McBride said, in general, people of faith were not meant to be the target of his satire.

"It was more about hypocrites and people who were saying one thing and living another," he said.

Celebrity preachers like Joel Osteen and T.D. Jakes have been fixtures of evangelical culture since the early aughts thanks to their massive congregations and strategic media presence, not to mention the Billy Grahams, Jerry Fallwells and Jim Bakkers that preceded them. But a new generation of Instagram-savvy preachers has made its way into pop culture, like Hillsong's now-disgraced Carl Lentz and Justin Bieber's pastor, Judah Smith.

With that fame comes scrutiny and the charge that their celebrity and wealth stand in contrast to the message of Jesus. But that disaffection with religious leaders that McBride exploits isn't new, says Kathryn Lofton, a professor of religious studies and American studies at Yale University.

"There's not a lot of very positive depictions of evangelists in American media in the last 50 years," Lofton said.

The Christianity of the Gemstone empire is anything but austere. The second episode of this season, for example, closes with Eli's kids hosting their extravagant annual give-a-thon in honor of their late mother's birthday.

"If the line's busy, call back. Somebody's gonna pick up. It might just be God," implores Uncle Baby Billy (Goggins). And what's a church service without a choir, dancing and, of course, jet packs?

For Deon Gibson, a graphic artist who used to work for pastor Paula White before she became the head of Donald Trump's White House Faith Office, the show is right on the nose.

"I knew those characters while I worked in the megachurches," he said. "Aside from the Hollywood theatrics, it is spot on. The conversations they have, the switching around of power and positions."

McBride did admit it was a difficult subject to satirize considering the viral videos that often surface showing similarly extravagant stunts and rock concerts being performed at church.

One comment on the show's subreddit shares a video clip of James River Church's annual Stronger Men's Conference in Missouri. "Thought this was a scene from the show at first," the commenter says of the massive pyrotechnics, monster trucks and acrobats descending from the ceiling.

"My biggest fear would be that we would put stuff in the show and then like months later before the show comes out you would like see a church actually doing something we were doing," McBride said. "You're like, 'I just hope people don't think we're ripping them off.'"

Adam Devine said he thinks making satire in general is a challenge right now.

"Some of the headlines in the news, you're like, well, that wouldn't even work because people would be like, 'That's too crazy,'" Devine said.

For all its critique and humor though, the series also infuses moments of tenderness and poignancy. One storyline that culminates in the series finale is Kelvin's struggle with his queer identity and his relationship with his partner.

"I hope that some kids who feel like hopeless and they're battling over whether they're gay or not, that this gives them a sense of hope that you can come out and be accepted by your family, by people within your church," Devine said. "Not everyone is going to turn their backs on you."

But Gibson, who still identifies as a believer but is no longer part of a congregation, thinks the show's depictions of the megachurch world might be a tough hurdle for some people to get over.

"I think it would offend some people, the honesty of some of the characters. But I like the show because I saw both sides. I saw that side of the ministry corruption, but at the end of the day, they were people," he said. "They were regular people who just got caught up in the fame and the money."